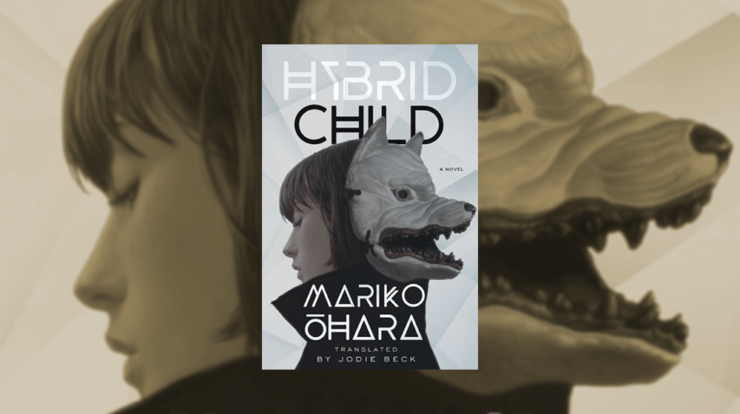

Hybrid Child by Mariko Ōhara is one of the few Japanese science fiction novels by a woman author that have been translated to English. It was originally published in 1990 and won the Seiun award the next year. The Seiun is the longest-lived and most prestigious Japanese SFF award; I’ve seen it called “the Japanese Nebula” because “seiun” means ‘nebula,’ but it’s more similar to the Hugo in that it’s an audience-voted award.

The translation (by Jodie Beck) just came out earlier this year, in the Parallel Futures series published by the University of Minnesota Press and edited by Thomas Lamarre and Takayuki Tatsumi. There aren’t that many university presses that have ongoing speculative fiction series, and I was intrigued by the previous starter volume of Parallel Futures: The Sacred Era by Yoshio Aramaki, even as I had some issues with it. So I picked up Hybrid Child too, and I was very surprised to find that it had very explicit transgender themes. In this novel, characters change gender, beings affect each other’s genders when they merge, and one character performs impromptu top surgery on herself due to dysphoria. There is also various moments of gender confusion in the narrative, even related to cisgender people—one of the early scenes features a woman general mistaken for a man until she shows up in person, for example. Let’s dive in!

While there are many central characters in Hybrid Child, the most central one is Sample B #3, a shapeshifting cyborg who was created as a war machine. Sample B #3 has the capability to assume the shape of different beings after sampling their tissues. Sample B #3 runs away from the military and samples various animals and at least one human, and initially identifies as male. Then—still early on in the book—he chances upon the rural house of a reclusive, misanthropic woman science fiction writer, and ends up sampling her daughter. The two of them merge, and his consciousness is eventually taken over by hers: Sample B #3 becomes Jonah, the young girl.

One of the major themes of this novel is abusive motherhood and child abuse. There is a lot of extremely heavy content, often written in ways that do not follow contemporary Anglo-Western plotlines and which might be relatively unexpected to the majority of English-speaking readers. Hybrid Child is not an easy read, neither emotionally nor structurally: the plot is likewise complicated, with one character living backward through time. But if you are willing to engage with all this complexity, there is a lot in the book that is fascinating and startling.

Sometimes Hybrid Child is shockingly prescient, even in odd little ways: “If you picked up an old telephone for example, you might be met with the sound of a crying baby. Then, you would be stuck inside the phone booth until you crooned some soothing words to make it stop – it was an old program from a private telecommunications company that had been used as a means to increase revenues.” (p. 181) If you have a child with access to an electronic device, you have probably come across online games that do exactly that. (“Stop playing the crying game!” is a phrase I have uttered too many times.) I had to put down the book multiple times in surprise, asking “REALLY, AUTHOR, HOW…?” – at one point we even see the anti-trans meme of the attack helicopter. I would say that Hybrid Child presents a subversion of it, except then the book would predate the material it subverts. Then again, an unusual form of time travel is one of the major plot elements…

Even in a broader context, there is so much that will be familiar to us, but was very much the future of the book’s present at the time it was written. Hybrid Child anticipates a whole range of Amazon products—obviously not named as such—from the Kindle to Alexa, and at one point, Ōhara’s version of Alexa goes haywire and starts rampaging through a planet. I feel that the author should probably have a long talk with Jeff Bezos.

Alas, there are also many aspects of Hybrid Child that will be problematic or difficult for contemporary readers. The book consistently conflates childbirth with womanhood. The essentialism of “all things that give birth are female” reminded me of attempts to include trans people in social activities by labeling them as women, regardless of whether they (we) are women. The book has a very expansive view of womanhood, one that even its own characters struggle with.

Buy the Book

Hybrid Child

These struggles interact with feelings of body dysmorphia and fat hatred, and are also related to puberty and sexual maturity. The shapeshifting protagonist Jonah tears her breasts off because she cannot deal with how her girl-shape is maturing and becoming a woman-shape, and gaining weight (p. 230). The text engages with some of these topics in depth, especially as they interact with womanhood, but presents some aspects—especially the internalized fat hatred—in a rather unconsidered way. Even though the book concerns itself with the concept of embodiment and explores related themes at length, it also plays all the “disfigured antagonist” tropes straight, which likewise bothered me while reading. And there is even more: to illustrate that one of the antagonists is well and truly evil, he is shown sexually assaulting and murdering a young girl, with the violence (though not the sexual aspect) depicted in graphic detail. The ero-guro aesthetic here might be seen as a break with the beautiful, melancholy decay of the book’s setting, but it directly continues the horror elements of the AI’s decline into calculated mass murder. (This torture scene is on pages 197-200, for those who would rather skip it.)

I found Hybrid Child extremely intriguing and densely layered both with ideas and with lyricism, though I also struggled with some elements of the book. I do think it is a very important work, and am happy that it’s finally available in English. It is one of those works that begs for detailed engagement from multiple viewpoints, and now with this translation, an all-new audience will hopefully have the access and ability to provide just that.

Also, I’m planning to switch things up after focusing on novels in the last few columns, so next time we’ll cover a short story collection—see you then!

Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person (e/em/eir/emself or singular they pronouns) currently living in the US with eir family and a congregation of books. Bogi writes, reviews and edits speculative fiction, and is currently a finalist for the Hugo, Lambda and Locus awards. You can find em at Bogi Reads the World, and on Twitter and Patreon as @bogiperson.